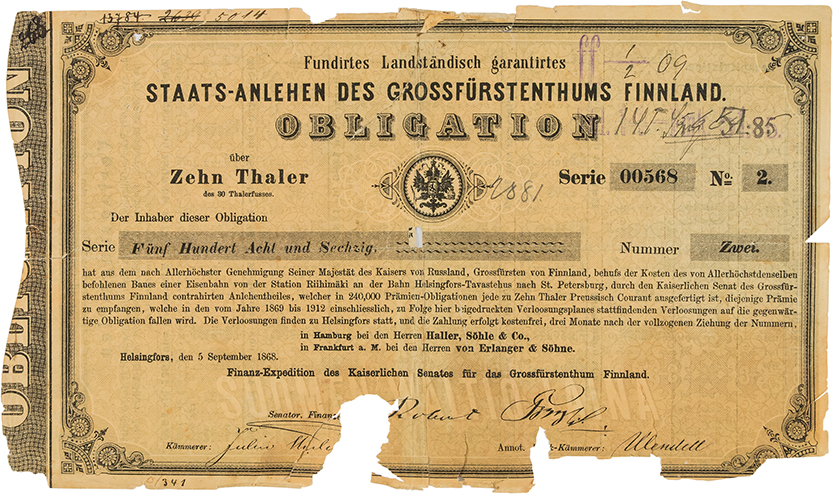

The Finnish economy started to grow strongly after the mid-1800s. The construction of the railway network played a key role in the reform of the economy. The railways made Finland into a more compact whole, as a country, and the Saint Petersburg railway also helped close the distance with the rest of the Russian Empire.

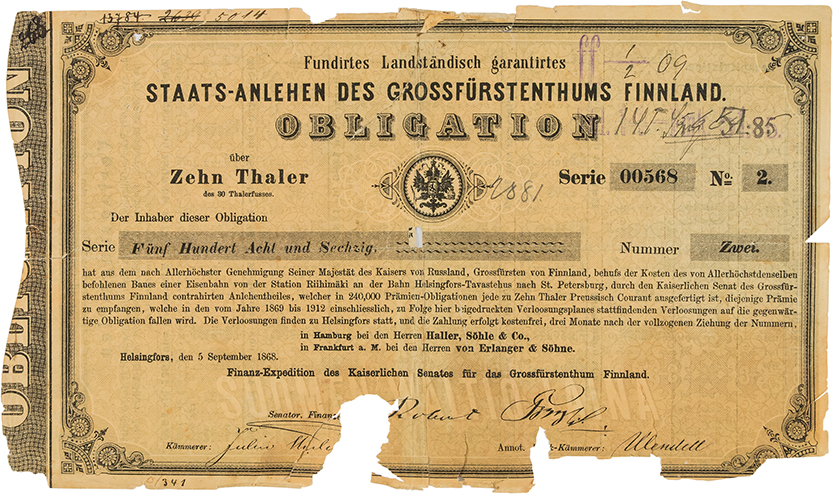

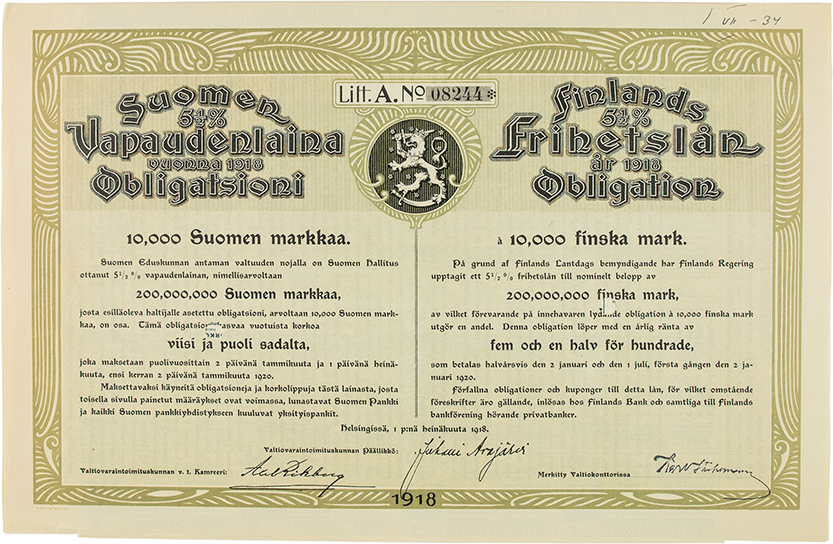

Bond from 1868 (St. Petersburg’s railway)

Lottery bond, 43.5 years, Prussian Thaler, intermediaries Haller, Söhle Co. ja von Erlanger & Söhne, signed by Robert von Trapp

The construction of the railways was almost entirely financed by foreign loans raised by the Finnish government. The Frankfurt-based trading house M.A. von Rothschild served as purveyor to the Senate of Finland from the issuance of the 1862 railway bond. During the bad crop years in the 1860s, the Senate also obtained a loan from the Rothschild family to cover the losses suffered due to the crop failure.

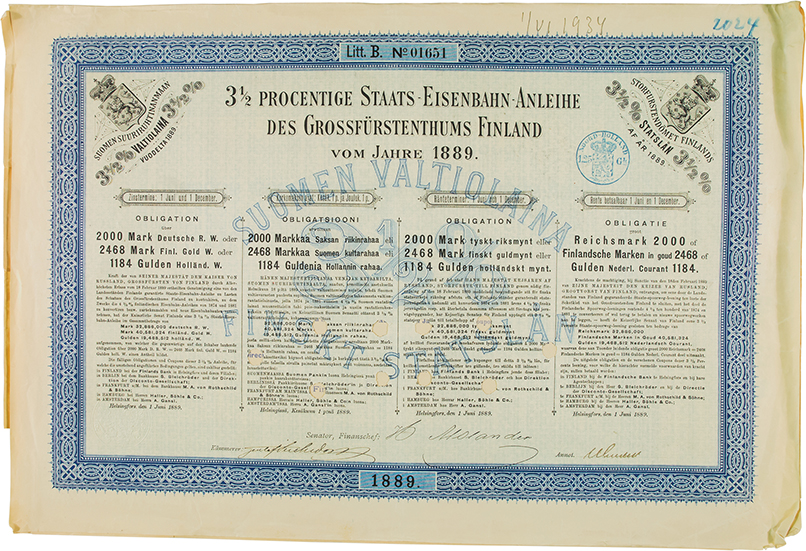

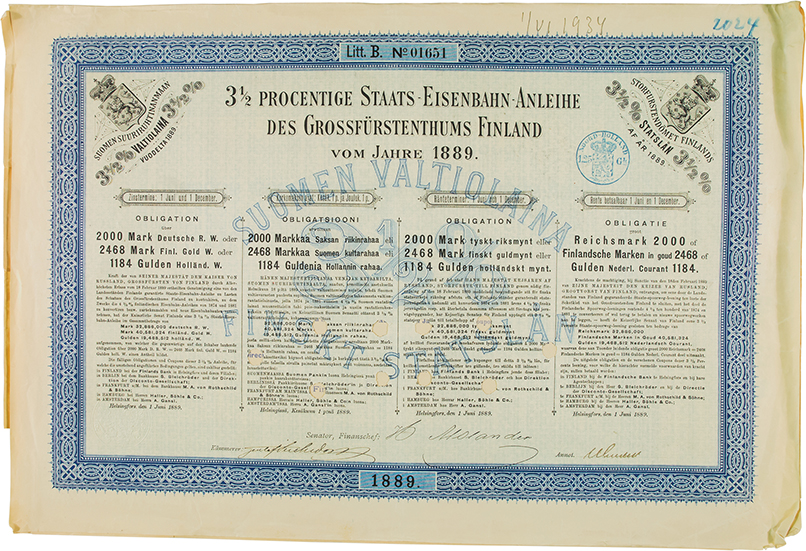

1889 railway bond (redemptions and Carelian railway)

1889 railway bond (redemptions and Carelian railway)

3.5%, 60 years, German mark, Finnish mark and Dutch guilder, intermediaries S. Bleichröder, Direktion der Disconto-Gesellschaft, M. A. von Rothschild & Söhne et al., signed by Herman Molander

The Rothschild House of Banking in Frankfurt was headed by Baron Mayer Carl von Rothschild, who was one of the most influential European bankers of his time. The Rothschild family owned banks in all the big financial hubs of Europe. The House of Rothschild was the best known European banking house in the 1800s, playing a major role in the growth of government bond markets, in particular, in the 1800s.

In the 1890s, the source of Finnish government borrowing shifted from German to French capital markets. Already before this, the Rothschild family had lost some of its influence on Finnish capital markets, with the passing away of Baron Mayer Carl von Rothschild, in 1886. The Frankfurt branch of the multinational banking house was closed down in 1901.